In Paris, where the scent of fresh baguettes mingles with the rustle of pages in a librairie on Rue de la Bûcherie, French literature has long served as a quiet but powerful mirror to the complexities of human desire. Unlike the sensationalism often found in Anglo-American portrayals, French writers have approached sexuality not as spectacle, but as a deeply personal, sometimes painful, always intimate force woven into the fabric of everyday life. From the dimly lit cafés of Saint-Germain-des-Prés to the quiet apartments of the Marais, French novels don’t just describe sex-they explore how it shapes identity, power, loneliness, and freedom.

Sexuality as Social Commentary in 19th-Century Paris

In the 1800s, Paris was a city of contradictions: revolutionary ideals clashed with rigid social codes, and the bourgeoisie hid their desires behind lace curtains. Writers like Gustave Flaubert didn’t shy away from this tension. In Madame Bovary, Emma’s affairs aren’t just about lust-they’re a rebellion against the suffocating expectations of marriage, class, and gender roles in provincial France. Her tragic end isn’t punishment for immorality; it’s the consequence of a society that offers women no real language for desire. Flaubert wrote this in Croisset, just outside Rouen, but the novel’s heartbeat is Parisian: the opera boxes, the boulevards, the salon conversations where passion was discussed in code.

Similarly, Honoré de Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine maps the sexual economy of Parisian society. Characters trade affection for status, marriage for inheritance, and seduction for survival. In Le Père Goriot, the daughter’s coldness toward her father mirrors the transactional nature of intimacy in a city where money dictates who gets to love-and who gets to be loved.

The Surrealists and the Liberation of Desire

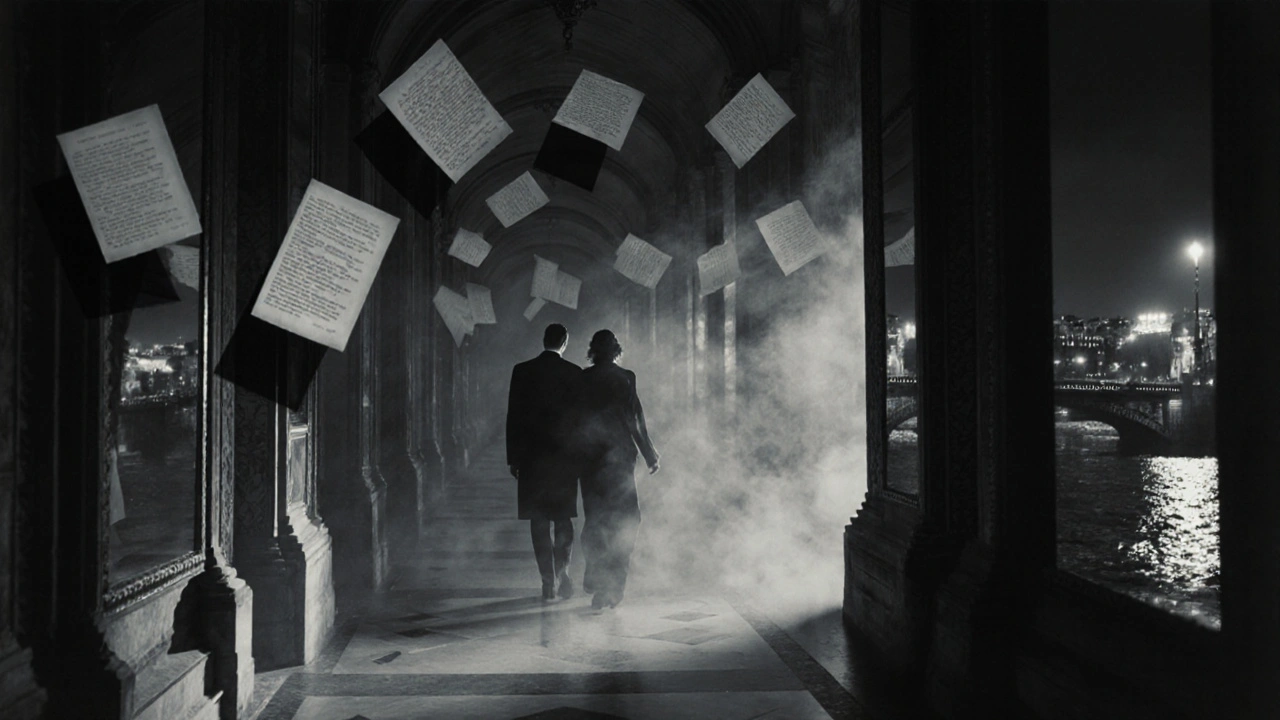

By the 1920s and 30s, Paris had become a magnet for artists and writers who saw sexuality as a path to truth. In Montparnasse, the cafés of La Rotonde and Le Dôme buzzed with conversations about Freud, the unconscious, and the political power of eroticism. André Breton, leader of the Surrealist movement, declared that desire was the only force capable of breaking bourgeois illusions. His novel Nadja is not a love story-it’s a map of obsession, chance encounters, and the erotic potential of the city itself. Nadja, the enigmatic woman he meets, appears in the shadows of the Palais-Royal, wanders through the catacombs, and vanishes into the fog of the Seine. Her sexuality isn’t defined by acts, but by mystery, autonomy, and resistance to being owned.

Simone de Beauvoir, who taught philosophy at the Lycée Molière in the 15th arrondissement, took this further. In The Second Sex, she didn’t just analyze women’s oppression-she showed how sexuality had been weaponized to keep women in their place. Her personal letters reveal how she and Jean-Paul Sartre practiced open relationships not as libertinism, but as a political act: to reject the idea that love must mean possession. In Paris, this wasn’t just theory-it was lived in the apartments of Saint-Germain, the bookshops of Left Bank, and the late-night debates at Café de Flore.

Contemporary Voices: Queer Identity and the Banlieues

Today, French literature continues to push boundaries. In the banlieues of Saint-Denis and Clichy-sous-Bois, writers like Fatou Diome and Léonora Miano explore how migration, race, and religion intersect with sexuality. Diome’s Le Ventre de l’Atlantique follows a Senegalese woman in Paris who finds freedom not in traditional marriage, but in solitary self-discovery-her sexuality becomes an act of resistance against both colonial expectations and patriarchal norms.

In the 2010s, queer writers like Jean-Paul Didierlaurent and Camille Laurens brought raw, unfiltered accounts of same-sex desire into mainstream French publishing. Laurens’ Dans ces bras-là tells the story of a woman’s obsessive love for another woman, set against the backdrop of the Parisian literary scene. The novel doesn’t romanticize-instead, it shows how desire can be messy, unreciprocated, and still profoundly transformative. These books are now stocked in the same bookstores that carry Proust: Librairie Galignani on Rue de Rivoli, Shakespeare and Company on the Left Bank, and even the smaller, independent shops like La Maison des Écrivains in the 11th arrondissement.

Why French Literature Gets Sex Right

What sets French literature apart isn’t its explicitness-it’s its honesty. French writers don’t treat sexuality as something to be conquered, marketed, or hidden. They treat it as a fundamental part of being human, as natural as hunger or grief. In Paris, where the concept of l’art de vivre still holds weight, sex isn’t separated from art, philosophy, or politics. It’s part of the same conversation.

Think of the way Marguerite Duras writes in The Lover: a teenage girl in colonial Indochina, but the emotional landscape is unmistakably Parisian-lonely, cerebral, and full of unspoken longing. Or how Annie Ernaux, in A Woman’s Story, describes her mother’s death and the sudden, shocking memory of her mother’s sexual past. Ernaux writes in plain, unadorned French-no metaphors, no flourish-but the emotional weight is crushing. That’s the French way: quiet, precise, devastating.

Where to Read These Books in Paris

If you want to experience this literature as it was meant to be read, find a quiet corner in a Parisian library or bookstore. The Bibliothèque nationale de France on Rue de Richelieu offers free access to rare first editions of Sade and de Sade’s letters. For contemporary works, visit the Festival du Livre de Paris at the Porte de Versailles each spring, where authors like Laurence Cossé and Édouard Louis read from their latest novels on sexuality and identity.

Or simply sit with a copy of Les Liaisons Dangereuses at a café table in the Luxembourg Gardens, watching the old men play chess and the students whispering in the shadows. You’ll understand then-sexuality in French literature isn’t about what happens between the sheets. It’s about what happens between the words.

Why is French literature considered more honest about sexuality than other cultures?

French literature doesn’t separate sexuality from philosophy, politics, or daily life. Writers like Flaubert, Beauvoir, and Ernaux treat desire as a lens to examine power, freedom, and identity-not as a tabloid topic. This comes from a cultural tradition where intellectualism and sensuality coexist, especially in Paris, where cafés have long been spaces for debate, not just coffee.

Are there modern French authors writing about LGBTQ+ sexuality today?

Yes. Writers like Édouard Louis, Camille Laurens, and Virginie Despentes have brought queer experiences to the center of French literary life. Louis’s Who Killed My Father blends memoir and political critique, exploring how homophobia intersects with class. Laurens’ Dans ces bras-là is a raw, unflinching portrait of lesbian obsession. Their books are bestsellers in Paris, translated worldwide, and taught in French high schools.

Where can I find original French editions of these novels in Paris?

For rare editions, visit the Bibliothèque nationale de France or Librairie Mazarine near the Luxembourg Gardens. For contemporary titles, head to Shakespeare and Company, Librairie Galignani, or smaller shops like La Maison des Écrivains in the 11th arrondissement. Many bookstores host author readings-check the Paris Book Fair calendar or the website of the Société des Gens de Lettres.

Is there a connection between French cuisine and the way sexuality is portrayed in literature?

There’s a subtle but real link. French literature often uses food and eating as metaphors for desire-think of the way characters savor wine, chocolate, or a perfectly ripe peach. This reflects a cultural view where pleasure, whether culinary or sexual, is meant to be savored slowly, with attention and ritual. It’s not about excess, but presence. In Paris, even a simple croissant au beurre is treated with reverence-just like the best scenes in French novels.

How has Paris changed as a setting for stories about sexuality over time?

In the 19th century, Paris was a city of secrets-affairs happened behind closed doors in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. By the 1960s, the Left Bank became a symbol of liberation, with open relationships and feminist discourse. Today, the city’s sexuality is more diverse: the 10th arrondissement’s queer bars, the immigrant communities of the 19th, and the digital dating scenes of the 13th all appear in modern novels. Paris still holds its mystique, but now it’s a city of many voices, not just one.